Trauma Bonding: Stages, Signs, Causes, and How to Break Free Safely

Summary

Trauma bonding explains why intelligent, capable people can feel emotionally trapped in relationships that harm their wellbeing. You may know something is wrong, yet feel unable to leave, detach, or move on. This is not weakness or poor judgement. It reflects how the nervous system adapts under prolonged emotional stress. This article explains trauma bonding clearly, how it develops, how it affects mental health, addiction, eating patterns, and physical health, and what genuinely supports recovery. Professional help is available ONLINE across Ireland and in person in multiple locations.

What trauma bonding really is

Trauma bonding is a powerful emotional attachment that forms when fear, emotional harm, or instability is repeatedly followed by moments of relief, reassurance, affection, or reconciliation.

In clinical practice, this pattern appears again and again. People often say they understand intellectually that the relationship is damaging, yet feel unable to step away. This is because the nervous system has learned that calm and relief only arrive through the relationship itself.

Over time, the brain associates attachment with survival. The body responds as if leaving is dangerous, even when staying causes harm. This is why trauma bonds feel intense, compelling, and deeply confusing.

In extreme situations this response has been described as Stockholm Syndrome. A more accurate understanding is appeasement. Appeasement is a survival response where the nervous system stays connected, compliant, or hopeful in order to reduce perceived threat. This response is automatic rather than chosen.

Trauma bonding is not a character flaw. It is biology responding to prolonged relational stress.

Trauma bonding versus love

Trauma bonds are often mistaken for love because they feel intense and emotionally consuming.

Healthy love is steady and predictable. You feel emotionally safe, even during disagreement. You do not have to manage another person’s emotions, suppress your needs, or constantly monitor your behaviour to maintain connection.

Trauma bonding feels urgent. Many people experience anxiety when contact reduces, emotional withdrawal symptoms, and overwhelming relief when the relationship briefly stabilises. That relief can be mistaken for closeness or intimacy.

From a nervous system perspective, relief following distress feels powerful. Over time, the body confuses relief with connection.

How trauma bonds develop over time

Trauma bonding develops gradually through repeated relational patterns.

There is usually a power imbalance. This may involve emotional control, finances, housing, communication, sexuality, parenting, or approval. One person adapts while the other sets the emotional climate.

There is alternating behaviour. Periods of criticism, withdrawal, intimidation, rage, or blame are followed by affection, remorse, gifts, or promises of change. The unpredictability strengthens attachment.

Over time, self-blame increases. Many people believe that if they explain better, stay calmer, love harder, or try more, the relationship will stabilise.

Eventually, people begin internalising the other person’s narrative. Memory becomes blurred. Incidents are minimised. Confidence in one’s own perceptions erodes. This loss of self-trust is a defining feature of trauma bonding.

Signs you may be trauma bonded

Trauma bonding often hides behind loyalty, endurance, and responsibility.

Common signs include feeling emotionally tied to someone who repeatedly hurts or controls you, defending behaviour you would never accept for someone else, feeling responsible for another person’s moods, leaving and returning multiple times, and experiencing anxiety or emptiness when contact reduces.

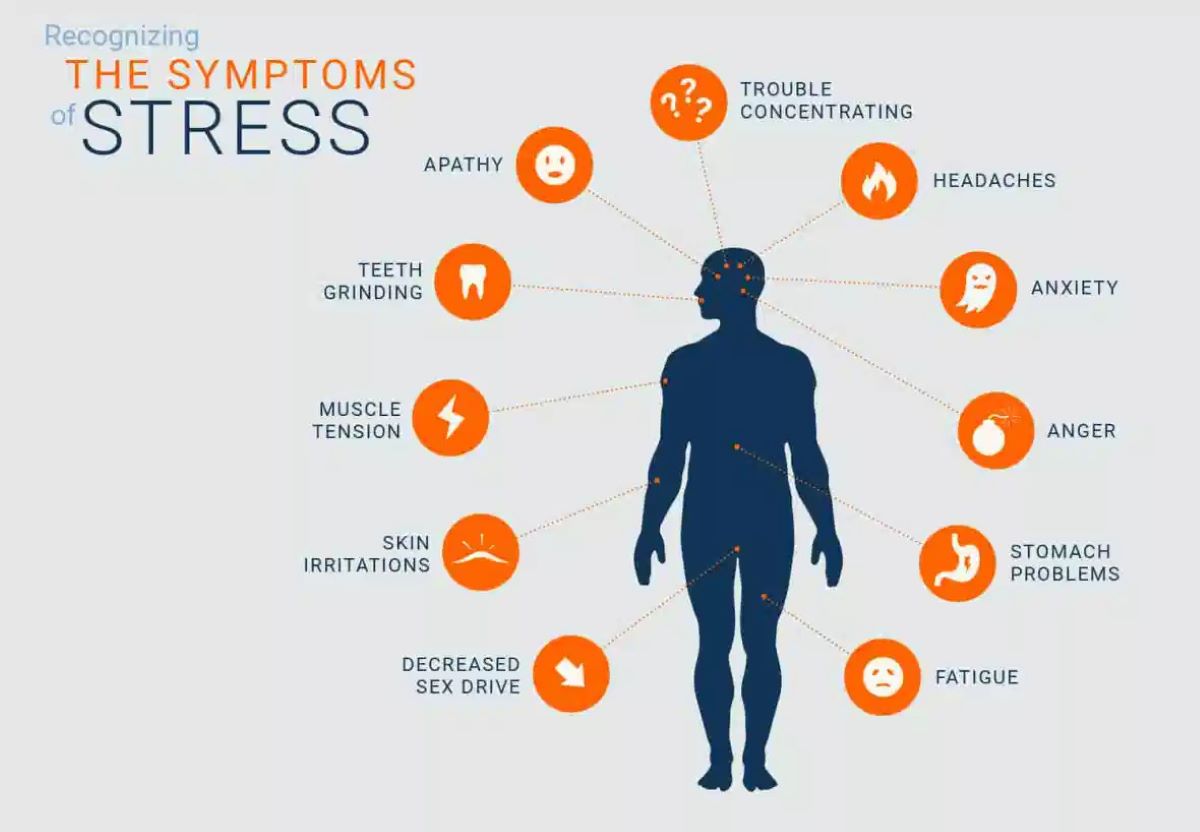

Physical symptoms are common. These may include poor sleep, digestive difficulties such as bloating or IBS, headaches, skin flare-ups, fatigue, sugar cravings, weight changes, and hormonal disruption. The body often carries what feels impossible to articulate.

Psychological patterns that keep trauma bonds in place

Certain relational dynamics reinforce trauma bonds.

Gaslighting undermines confidence in your own perceptions.

Intimidation, even when subtle, keeps the nervous system in threat mode.

Emotional unpredictability creates confusion alongside hope.

Fear conditioning makes staying feel safer than leaving.

When these patterns repeat, clarity becomes difficult. Many people describe knowing something is wrong while no longer trusting themselves.

Trauma bonding and addiction patterns

Trauma bonding and addiction frequently overlap. In clinical work, this connection is striking.

Both operate through cycles of distress followed by temporary relief. Both are driven by nervous system dysregulation rather than lack of willpower.

People in trauma bonded relationships may develop or relapse into addictions as a way of coping with chronic emotional stress and self-abandonment. Common patterns include alcohol misuse, drug use including prescription medication misuse, nicotine and vaping, gambling addiction, pornography and compulsive sexual behaviours, shopping or spending addiction, work addiction, exercise addiction, gaming, and online dependency.

In some relationships, addiction is actively exploited. Substances or behaviours may be encouraged, criticised, or weaponised as a means of control, deepening dependence and confusion.

Trauma bonding and eating disorders

Eating disorders and disordered eating patterns are another common outcome of trauma bonding.

Emotional eating, binge eating, restrictive eating, bulimia, orthorexic patterns, and sugar addiction often emerge when emotional safety is absent. Food can become a way to regulate distress, reclaim control, or soothe exhaustion.

Digestive symptoms, blood sugar instability, fatigue, weight changes, and hormonal disruption frequently improve when relational stress is addressed alongside appropriate nutritional support.

Trauma bonding and physical health

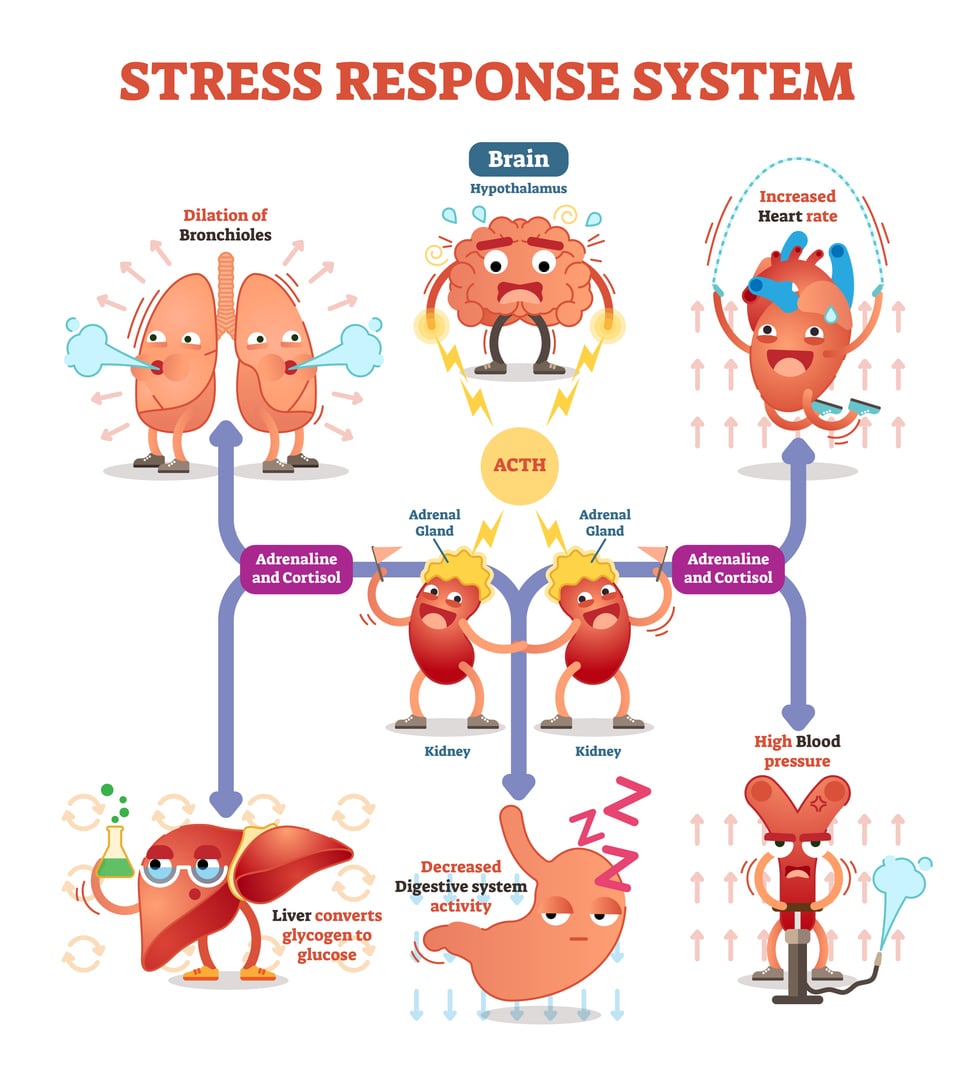

Living in a constant state of emotional threat keeps the stress response activated.

Over time this can affect sleep quality, gut health including reflux and IBS, thyroid balance, PMS, perimenopause, fertility, immune resilience, inflammation, energy levels, concentration, and memory.

For people living with autoimmune conditions, chronic pain, fatigue, ADHD, or neurodivergence, prolonged trauma bonding can significantly intensify symptoms. This reflects biology under sustained pressure rather than personal weakness.

Trauma bonding, ADHD, and neurodivergence

Adults with ADHD and other neurodivergent profiles may be particularly vulnerable to trauma bonding. Emotional intensity, rejection sensitivity, impulsivity, and earlier relational injuries can increase risk.

Support needs to be paced, validating, and practical. Neurodivergence is not the problem. Unsafe attachment dynamics are.

How to begin breaking a trauma bond

Breaking a trauma bond is a process rather than a single decision.

Naming the pattern clearly is often the first step. Writing down behaviours over time helps restore self-trust.

Safety comes first. Practical planning, secure communication, trusted contacts, and professional guidance matter. If there is immediate risk, emergency services or specialist domestic abuse supports should be contacted.

Reducing isolation is crucial. Trauma bonds thrive in secrecy. Gradual reconnection with safe people supports nervous system regulation.

Individual counselling and psychotherapy help rebuild emotional stability. Clinical Medical Hypnotherapy and RTT can calm deeply embedded survival responses. Nutrition support can stabilise energy, digestion, and blood sugar during periods of change.

Couples therapy is not appropriate where fear, coercion, or abuse exists. Individual support is the correct starting point.

What recovery actually looks like

Recovery is rarely linear. Relief and grief often coexist.

Missing the good moments does not mean the relationship was healthy. It means the nervous system is recalibrating. With appropriate support, people often notice improved sleep, steadier digestion, reduced anxiety, clearer thinking, and renewed confidence. The body begins to settle as safety returns.

Supporting someone who may be trauma bonded

If someone you care about may be trauma bonded, avoid pressure or ultimatums. Listen without judgement. Stay consistent. Offer practical support. Leaving is often a staged process rather than a single event.

Your presence matters.

About the Author

Claire Russell is a Counsellor and Psychotherapist, Clinical Medical Hypnotherapist, Rapid Transformational Therapist, Advanced Rapid Transformational Therapist, and Qualified Registered Nutritionist with over 20+ years of clinical experience.

Support and therapy is available through Counselling, Psychotherapy, Clinical Medical Hypnotherapy, RTT, Hypnotherapy for addictions, Hypnotherapy for weight loss, Hypnotherapy for anxiety, stress, trauma and related difficulties, alongside Registered Nutritionist services. Appointments are available ONLINE nationwide and in person in Adare, Newcastle West, Limerick, Abbeyfeale, Charleville, Kanturk, Midleton, Youghal, Cork, Dublin, and Dungarven.

Book a Consultation Now

Claire Russell Therapy

Phone: 087 616 6638

Email: clairerusselltherapy@gmail.com

Website: clairerusselltherapy.com

Educational note

This article is for educational purposes only and does not replace medical, legal, or safeguarding advice.

References

- Dutton DG, Painter S. Emotional attachments in abusive relationships. Violence and Victims. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8193053/

- Herman JL. Trauma and Recovery. Basic Books. https://www.basicbooks.com/titles/judith-lewis-herman/trauma-and-recovery/9780465087303/

- van der Kolk B. The Body Keeps the Score. Penguin. https://www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/216537/the-body-keeps-the-score-by-bessel-van-der-kolk-md/

- Carnes P. The Betrayal Bond. Health Communications. https://www.healthcommunicationsinc.com/product/the-betrayal-bond/

- NICE. Post-traumatic stress disorder guideline NG116. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116

- World Health Organization. Violence against women. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

- Volkow ND, Koob GF. Brain disease model of addiction. NEJM. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1412090

- Treasure J, et al. Eating disorders. The Lancet. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30059-3/fulltext

- Schore AN. The Science of the Art of Psychotherapy. Norton. https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393706642

- Porges SW. The Polyvagal Theory. Norton. https://wwnorton.com/books/9780393707007